When you see the graceful curves and spirals carved into wood, woven into cloth, or painted on a torogan’s beam, you’re witnessing more than decoration — you’re seeing the heartbeat of a people. Among the Maranao, these intricate designs are known as okir (or ukkil), a visual language that has told stories for centuries.

A Language Without Words

Okir is not just art — it’s identity. The word itself means “to carve” or “to engrave,” but its meaning goes far deeper. For the Maranao people of Lanao, okir is a way of expressing worldview, spirituality, and social harmony through pattern and form. Every swirl, leaf, and curve carries memory — of ancestry, of home, of Lake Lanao’s still waters and the stories whispered by its winds.

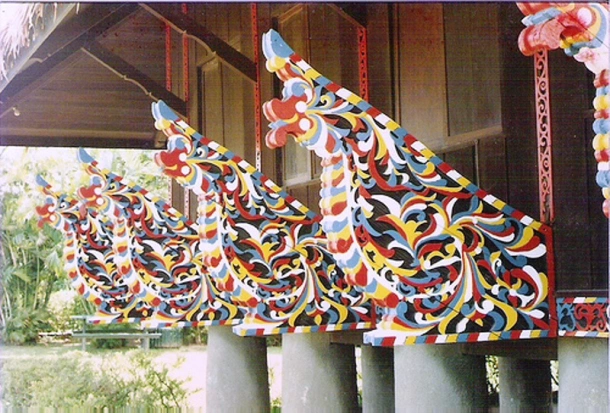

Traditionally, okir adorned torogan houses, the grand ancestral homes of Maranao nobility. The famous panolong — the protruding beam of the torogan — features elaborate okir carvings that symbolized strength, prestige, and artistry. These designs weren’t chosen randomly; each one spoke of the owner’s status, lineage, and respect for tradition.

The Two Faces of Okir: Male and Female Designs

Maranao artisans often speak of two styles of okir — one masculine (okir-a-dato) and one feminine (okir-a-bae).

- The masculine designs feature bold, angular lines and symmetrical patterns — often representing courage, leadership, and structure.

- The feminine designs, in contrast, are softer, curvier, and more flowing — symbolizing grace, beauty, and nurturing.

Together, they balance each other, much like the dual forces that sustain life. This harmony reflects the Maranao philosophy that beauty lies in balance — not dominance.

The Sarimanok and the Flow of Life

One of the most well-known elements found in okir is the sarimanok — the mythical bird believed to bring good fortune. Often depicted with a fish in its beak, the sarimanok represents prosperity and the connection between the spiritual and earthly realms. Its feathers flow into okir-like motifs, blending seamlessly with leaves and vines.

Many designs in okir also echo natural forms — vines (pako-rabong), buds (pako), and waves (dilom-dilom). These organic lines remind the viewer that everything in life — art, nature, and faith — is interconnected. To carve or weave okir is to participate in that eternal flow.

More Than Decoration: A Symbol of Survival

Beyond its beauty, okir has also become a symbol of resilience. Through years of change — from colonial influences to modernization — Maranao artists have kept the tradition alive. You’ll still see okir today in Tugaya, a town renowned for its woodcarvers, brassworkers, and weavers. Here, artisans pass on their skills through generations, each curve carved by hand and heart.

In recent years, young Maranaos have reimagined okir for the modern world. You’ll find it printed on clothes, jewelry, murals, and digital designs — proof that tradition can evolve without losing its soul. The motif that once adorned royal houses now proudly decorates t-shirts, bags, and university halls, continuing its story in new forms.

Okir as a Way of Seeing

To understand okir is to understand the Maranao worldview: beauty as order, art as heritage, and tradition as living wisdom. The motif doesn’t just fill space — it tells stories, connects generations, and honors the unseen.

When a craftsman carves okir, they don’t merely shape wood; they recall ancestors. They turn memory into form. Every spiral and flourish becomes a reminder that culture is not something to preserve in a museum — it’s something to live every day.

Carving the Future

As Maranao artists and storytellers continue to share their heritage, okir remains a proud symbol — a bridge between past and present, tradition and innovation. It reminds us that culture, like a vine, grows stronger when it keeps reaching toward the light.

So the next time you see a piece of okir — whether on a torogan’s beam, a brass gador jar, or even a phone case — take a moment to look closely. Behind those patterns lies the enduring rhythm of Maranao life, carved by hand, guided by heart, and kept alive by generations who refuse to let their story fade.